“Is amhlaidh atá Gaeil na haimsire seo agus a bhformhór ceannaithe ag Gallaibh. Ní heol dóibh gurab amhlaidh atá, ach is ea. Táid tar éis a díolta féin ar ór agus ar airgead nó ar luach óir agus airgid. Tá an fear saibhir tar éis é féin do dhíol ar mhórán, agus tá an fear daibhir tar éis é féin do dhíol ar bheagán”.

“Is amhlaidh atá Gaeil na haimsire seo agus a bhformhór ceannaithe ag Gallaibh. Ní heol dóibh gurab amhlaidh atá, ach is ea. Táid tar éis a díolta féin ar ór agus ar airgead nó ar luach óir agus airgid. Tá an fear saibhir tar éis é féin do dhíol ar mhórán, agus tá an fear daibhir tar éis é féin do dhíol ar bheagán”.

Sin mar a scriobh an Piarsach sa bhliain 1912. Ach ní raibh sé gan dóchas, mar san alt céanna dúirt sé:

“Tá drong bheag de Ghaelaibh nach bhfuil ceannaithe agus is chucu sin atáimid”.

Ní bhfuair Gaeil a saoirse i 1922 ná ó shin. Táid fós faoi cheannas Gall agus tá comharthaí agus torthaí an éigirt sin go follasach in Éirinn an lae inniu.

Le foilsiú an pholasaí seo ÉIRE NUA tá an Barr Bua á sheinm arís agus tá an meirge á ardú. Tá idir anailís agus treoir sa cháipéis seo. Déanaimis staidéar uirthi agus gríosaímis clanna Gael chun misnigh agus chun saohair.

A New Beginning

A New Beginning

Ireland in its national experience is unique in western Europe. The country’s history as a colony of England has left its mark on Irish political, social, economic and cultural life.

Though the Ireland we have inherited has all kinds of resources and great potential for national achievement, it is far from realising that potential. Ireland is marked by underdevelopment, unemployment, emigration, poverty on a large scale, and a huge national debt. These problems, serious enough in themselves, are magnified by the continuing conflict in the Six Counties, which also has its origins in Ireland’s colonial history.

A realistic assessment of Ireland’s condition in 2000 shows that we have enormous problems, two failed states, and a political system that perpetuates our plight. One great obstacle to changing all that is our lack of hope. Another major obstacle is the slave mentality engendered in many of our people by centuries of conquest.

Yet the ideal of an independent Irish republic — the ideal proclaimed by the leaders of the 1916 Rising 80 years ago — still inspires those who continue the struggle for national unity and freedom. From the wellsprings of that ideal we can draw hope, inspiration and determination to forge a New Ireland — making a new beginning, based on sound principles and a realistic plan, through the Éire Nua programme.

This programme can be our instrument to build a sound future for our nation. The programme embraces all the people of Ireland; it provides for a system in which all creeds and traditions can be represented and all citizens can exercise real power, without any group infringing on the rights of others. The alternative to the forging of a New Ireland is to endure the present affliction — perhaps in the blind hope that our politicians and their EU friends will somehow magically find ways to transform our present debilitated, impoverished and undemocratic society into a nation that is strong, prosperous and democratic. But what makes that a wholly unrealistic expectation is that these politicians, the system they sponsor, and the policies they sustain and operate, are themselves at the core of the problem that confronts us. We know from bitter experience that Ireland has no real future under the direction of such politicians.

The system of partition government in Ireland has been maintained since 1922, and since 1973 under the growing influence of the EU. It is an inescapable fact, on the supreme test of results, that this system has failed. It is time to think of radical change.

The Éire Nua programme provides for a strong provincial and local government in a federation of the four provinces, designed to ensure that every citizen can participate in genuinely democratic self-government, and to guarantee that no group can dominate or exploit another. Under this programme all traditions in Ireland can make a valuable contribution to the nation. The programme and its structures will make it possible to bring together all the positive forces in the country. Éire Nua will provide the basis for implementing progressive social, economic and cultural policies.

Like other peoples, the Irish have their virtues as well as their faults. Irish men and women have made their mark throughout the world in many fields of endeavour. They have contributed in great measure to the development of America, Canada, Australia, and other countries. The Rising of 1916 and the Irish War of Independence inspired whole nations, particularly in Africa and Asia, to throw off the yoke of colonial oppression. In the light of these achievements, and of the spectacular recent advances of national rights and democracy in eastern Europe, it is tragic that the shackles still binding Ireland to its colonial past have prevented us from developing our nationhood.

So we must work to liberate the Irish people and establish a democratic system, based on justice and equal rights — to build Éire Nua: a New Ireland . In that Ireland, Irish people will begin to experience real power in their own communities, with those communities serving as the foundation for a modern, pluralist Irish republic.

The programme is available for wide distribution, study and debate throughout the country and among our exiled children.

______________________________________________________________

Éire Nua – A new Ireland

Introduction

Irish people have demonstrated a native talent for formulating unusually effective policies for government and social administration. We have seen this, for example, in the Brehon Laws, which were in force in Ireland from the eighth to the sixteenth century, and in the dramatic influence exercised by the emigrant Irish on the constitutions and politics of the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, Burma, and various African states.

The creative political genius of the Irish has flourished abroad; sadly the same cannot be said for Ireland itself, especially during the years since 1922.

There is an Irish nation which is based on an organised society and distinctive culture, with roots stretching back more than 1,500 years. This Irish nation has long endured invasion and colonisation by a more powerful neighbor. For more than 800 years the Irish people have heroically resisted this aggression and each generation handed on the torch of liberty to the next. Over the centuries the descendants of many of those who came as conquerors were assimilated and were accepted as Irish. Some of the Anglo-Norman families, for instance, became “more Irish than the Irish themselves” and have made an enormous contribution to Irish life, including the struggle for freedom.

Irish Republicanism has its roots in the desire for separation from England and the right of the Irish people to the ownership and control of their own country. Since the 1790s it has developed and evolved on the basis, not merely of separatism, but also of democracy and inclusivity based on the Rights of Man.

In the great Rising of 1798 large numbers of Protestants, Catholics and Dissenters fought side by side as United Irishmen to break the connection with England and establish an Irish Republic. That effort to achieve freedom and equality was brutally suppressed and the Act of Union creating the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was enacted in 1800. Throughout the nineteenth century it was a deliberate policy of English governments to cultivate loyalty to the Crown as well as bigotry and Orangeism among the mass of the Protestant people. They found allies also among some of the emerging Catholic professional and merchant classes. The unionists of Ulster (nine Counties) were allowed to exercise a veto over the demand of the majority of the Irish people for Home Rule and later for an Irish Republic.

From 1798 on the Republican non-sectarian position was resolutely maintained by men and women of vision and courage. The Irish Republic proclaimed in arms in 1916 was endorsed by a solid majority vote of the Irish people in 1918 and the first Dáil Éireann, embracing all 32 Counties, was established in 1919. England’s response was to declare the Irish parliament illegal and to unleash forces of terror on the Irish people and their institutions.

The Republic guaranteed “religious and civil liberty, equal rights and equal opportunities to all its citizens . . . cherishing all the children of the nation equally, and oblivious of the differences carefully fostered by an alien government, which have divided a minority from the majority in the past” (1916 Proclamation).

From 1916 to 1921 the Irish Republic was stoutly defended against English forces and a civil administration was organised. Under threat of “immediate and terrible war” and with the compliance of a section of the Republican Movement, Ireland was partitioned and Ulster was divided in 1921-22.

The legal instrument used to achieve this was the Westminster Government of Ireland Act 1920. The two States which exist in Ireland today date from that time. The Six-County State was created by arbitrarily dividing the historic province of Ulster, based on a sectarian head-count, designed to produce a permanent unionist majority within the ‘United Kingdom’ — now “of Great Britain and Northern Ireland”. Thus was the Irish Republic proclaimed in 1916 and democratically endorsed in 1918 overthrown and two Partition States established to supplant it.

As we enter the twenty-first century, Ireland is a divided country. Six counties, containing nearly one-third of the total population of Ireland, are under an English administration whose power in Ireland is maintained by heavily armed forces of occupation. These two Partition States have been marked by emigration, poverty and economic imbalance over the decades since 1922. Normal democracy has been impossible in the artificial Six-County State. Political instability and repressive laws, a paramilitary police force, gerrymandering of electoral boundaries and discrimination in employment and housing have all been used to ensure that this part of Ireland remains within the ‘United Kingdom’.

During the many centuries of English rule Ireland was administered as an integral political unit. In 1918, in the last all-Ireland election, the Irish people voted overwhelmingly for the political unity and sovereignty of Ireland. The rejection of unionism by the vast majority of Irish people is again clearly shown in the map, based on the results of the 1997 Six-County local elections.

______________________________________________________________

A new electoral map of the Six Counties

This map gives a visual impression of the very extensive nationalist rejection of union with Britain. Even within unionist majority areas there is a considerable and often strong anti-union vote — in the region of 39 per cent in Belfast and Craigavon and as high as 45 per cent in Armagh.

When this map is placed where it belongs — within a map of the thirty-two counties of Ireland — the unionist enclave is revealed for what it is: a small area in north-eastern Ireland.

Yet from its north-eastern redoubt the unionist minority has exercised for nearly eighty years a sweeping veto over the political will of the overwhelming majority of the Irish people. This anti-democratic faction is underpinned in its power in the north-east by the guarantees of the Westminster government. In the Hillsborough Agreement of 1985 and again in the Belfast Agreement of 1998 this minority veto was guaranteed by the Dublin administration as well, in further violation of Ireland’s 32-County sovereignty.

______________________________________________________________

A failed arrangement

The failure of the Partition arrangement is evident from nearly eighty years of “the nationalist nightmare” in the north-east — occupation, repression, thought control, economic stagnation and emigration and from the British government’s abolition of the Six-County Stormont parliament in 1972. Subsequent solutions, such as the 1973 Sunningdale Agreement and the 1985 Hillsborough Agreement, have underlined the failure of Partition.

The current policy, based on the Belfast Agreement signed at Stormont on April 10, 1998, seeks to make the artificial Six-County State work within the ‘UK’ by an elaborate and convoluted system that has been labelled “power-sharing”. Since this agreement did not address the basic problem of English rule in Ireland it was flawed from the start. It was sold to the electorate as a basis for a permanent peace, which it could not deliver. It was dishonest, in that it was sold to unionists as a deal to consolidate the union with England and simultaneously urged on nationalists as something which would weaken the union and lead to a united Ireland. And the unionist veto was endorsed, allowing 18% of the population of Ireland to dictate the political progress of the other 82% and therefore of the nation as a whole. As in the case of the Treaty of Surrender in 1921 this Agreement was put to the people as a question of war or peace. Accordingly it was not a free vote; also, a majority in the Six Counties was stated to be decisive for all Ireland.

English rule in Ireland is an injustice, an infringement of Irish national sovereignty, which can be ended only by an administration in Westminster which decides to disengage and withdraw from Ireland. Anything less than such a disengagement will only prolong the political instability and lead inevitably to further armed resistance.

The 26-County State has cooperated in the deception of the Belfast Agreement and has thus sought to legitimise foreign rule in Ireland. Some 26-County politicians hanker after a return to membership of the British Commonwealth. In all of this they are aided and abetted by individuals of wealth and influence, and by some people in the media. These same politicians operate a “clientelist” system; public office is achieved and maintained by buying people’s allegiance, trading favours for votes. Corruption in finance, politics and physical planning is rife and the resultant public cynicism has led to a decline in the exercise of the franchise by citizens who feel increasingly powerless.

This culture of corruption is a consequence, not merely of personal dishonesty on the part of certain individuals, but also of the highly centralised nature of the 26-County State, whereby decisions affecting the everyday life of communities are placed in the hands of an elite cadre of politicians and bureaucrats.

Enormous sums of money have been borrowed to perpetuate this system and this has created one of the highest per capita debts in the world. There has also been a deterioration in the Irish public services — health, education and social welfare. Disillusion and frustration with the prevailing conditions have led in some sectors to a near-breakdown of social order, particularly among young people in urban areas. The Irish people deserve better government than this. They deserve leaders who are imbued with sound moral values and who are interested in genuine public service, rather than self-aggrandisement and power for the sake of power. Our long struggle for freedom provides us with endless examples of selfless men and women who dedicated their lives to the welfare of our people.

_______________________________________________________________

Cultural and economic consequences

These problems have been compounded by policies of cultural deprivation, with Irish identity and the Irish language deliberately downgraded. The only culture many young Irish people know is a commercialised Anglo-American pop culture, and they are denied access to any real knowledge of Ireland’s long history of struggle for freedom. For years now the people of the 26 Counties have been paying more per capita for the maintenance of the Six-County Border than have the people of Britain. Yet the continued British presence in the North, and British influence in the South, have brought only tragedy and a scandalous waste of resources.

The Partition of Ireland led to a dissipation of scarce resources north and south. There has been no unified long-term capital investment in areas like energy, education, health and industry; there has been great duplication of expenditure. The impact of Partition on areas of Ireland along the British-imposed Border has been particularly injurious.

British systems of government and economic management, inappropriate for a country of our size and economic condition, have been slavishly perpetuated, north and south, since Partition. Other small countries in Europe, some with fewer natural resources than Ireland’s, have made great economic strides in modern times, particularly since WWII, and have achieved high standards of living for their people. The unemployment, poverty and emigration the Irish have experienced would be completely unacceptable in Sweden, Switzerland or Finland; they should also be unacceptable here.

_______________________________________________________________

EU membership

Our problems were magnified when both states were led into full membership of the so-called “European Community”. Such membership was unsuited to a country at our early stage of economic development — the result of Ireland’s being a British colony for centuries. No modern nation has managed to bring itself from underdevelopment to full development in circumstances of unrestricted free trade — a situation that in Ireland’s case is compounded by continued foreign occupation.

Under the Act of Union of 1800 Ireland lost half its population and suffered dire poverty and stunted growth. In the early twentieth century Ireland attempted to break entirely with Britain; but under the Partition arrangement the malign influence of British power has persisted for nearly eighty years. This influence persists within the neo-colonial framework of the EU.

Since 1972, when we were promised “markets in Europe and jobs at home”, native manufacturing industries, never designed to withstand competition from heavily bankrolled multinational European industries, have been shut down. EU agricultural policy has resulted in elimination of family farms, with detrimental social consequences for rural communities.

Agricultural policy is almost totally dictated by Brussels. It has favoured the wealthier farmers and has even ordered Irish citizens to take some of their land out of production. So many have now left the land that schools and post offices are being closed down and some rural parishes even have difficulty in fielding a sporting team. This has all undermined people’s idea of self-sufficiency, and the resultant movement to urban areas has increased the culture of dependency, creating new problems in the towns and cities.

Sinn Féin Poblachtach regards the European Union, as it has developed and continues to develop, as a modern form of imperialism.

It serves the interests, above all, of big business and the super-rich. Corruption is rampant there also as we saw in 1999 when the whole EU Commission had to resign. It is undemocratic in its institutions and it is overcentralising; in this it runs counter to the Republican aims of increasing the democratic power of citizens and decentralising decision-making to manageable units where all citizens can participate in a meaningful way.

It is sometimes remarked that the EU has promoted progressive policies in Ireland, like equal pay for equal work and protection of the environment. These are steps which any Irish administration could have taken at any time. Our standards should be even higher than those imposed by Brussels.

The Celtic Tiger economy has served to provide more jobs, but those who benefit most from it are those who are already rich. In recent years the gap between rich and poor has widened. There is more social exclusion and rates of real poverty and illiteracy are actually getting worse. A crisis in housing our people is with us.

Whatever economic improvements we have witnessed have been brought about by the transfer of structural and other funds by the EU and by the driving force in economic development which is based on encouraging multinational companies to locate in Ireland. This is not the solid foundation on which to build a national economy.

Too many people have been left on the margins of society and a sub-culture of poverty has been generated. Economic development based on inward investment by multinational companies means that there is no indigenous input and there are no roots in the communities. The factors which sustain such an economy are totally beyond the control of the Irish people.

(The Sinn Féin Poblachtach perspective on social and economic questions is presented in our policy document SAOL NUA.)

Sinn Féin Poblachtach recognises the enormous influence of modern technology, especially mass communications which have made the world smaller. We also recognise the interdependence of peoples and our duty to play a positive role in international affairs. But an over-emphasis on economic development, based on a rapacious exploitation of the world’s finite resources and measured by growth in GNP, is inadequate. Recent United Nations Human Development Reports on Ireland have shown just how deficient such an approach is, resulting in social exclusion, poverty and illiteracy, which in turn denies many thousands of people the rights of full citizenship and leads to escalating crime.

Both states in Ireland boast of increasing the number of police and building new prisons. The suicide rate has been growing at an alarming rate. These are hardly the signs of a healthy community.

Ireland, with its historic experience of English colonisation and exploitation, has much in common with former European colonies in the Third World. We can best serve the interests of our own people and of humankind by maintaining a principled non-aligned stance in international affairs, avoiding military alliances and promoting the cancellation of Third World debt. Our democratic and egalitarian principles and our own long struggle for national independence should lead us to promote human rights and the liberation of people everywhere.

_______________________________________________________________

A new beginning

The following proposals indicate ways to remedy Ireland’s weakened and wasted conditions and gradually bring the nation to its full health. These proposals aim to abolish the failed, undemocratic system of Partition rule, and to replace this with a democratic system based on the unity and sovereignty of the Irish people, as well as on their right as free citizens to equal treatment and equal opportunity. After decades of armed conflict and political turmoil — and given the clear failure of the British-model systems now in operation to provide adequate and improving standards of living — there is an obligation on all Irish people to work together to find a new, constructive way forward. Our nation is made up of diverse traditions, each of which can make a valuable and positive contribution to the community as a whole.

The structures which we propose are designed to embrace and include all the people of Ireland, on the basis of “cherishing all the children of the nation equally”. Dáil Uladh and the regional and local structures in Ulster will ensure that both unionists and nationalists can have access to power — real power.

A federal structure involves a sharing of sovereignty, and Dáil Uladh would have more power than the old Stormont ever had. Similarly in the other three provinces, all communities and citizens would have access to real power.

What we seek to establish is a pluralist participative democracy with appropriate structures at every level in society. When the malign influence of Westminster rule is removed at last a New Ireland can be fashioned by the Irish people themselves, of all persuasions. A federal system, with strong regional and local government, will make it possible for unionists and nationalists to co-operate in the common interest, pooling the talents of all and working together to build a new and prosperous Ireland.

As we enter the twenty-first century it is finally time for the Irish people to apply their undoubted creative genius, and the talent for government that they have so often demonstrated abroad, to the needs of the Irish nation at home.

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

Proposed Governmental Structures

The object of Sinn Féin Poblachtach is to establish a new society in Ireland: Éire Nua. To achieve that, the structures of undemocratic partition rule must be abolished; they must be replaced with entirely new structures based on the unity of the Irish people as a whole. The new system would embody two main features:

- a new constitution;

- a new government structure.

A new constitution

The new constitution would provide for;

a. Charter of Rights, to secure for citizens effective control of their conditions of living, subject to the common good;

b. structure of government designed to provide the maximum distribution of authority at provincial and subsidiary level;

c. the right of Ireland to join international organisations — eg the United Nations, the World Health Organisation — so long as such organisations do not subvert Irish sovereignty or neutrality.

Draft Charter of Rights

A Charter of Rights would be formulated, along these lines:

We the people of Ireland are resolved to establish political sovereignty, to secure human justice and social progress in this island, to achieve a better life for all, and henceforth to live in peace with one another. And so we declare our adherence to the following principles:

- Article 1. Every citizen is born free and equal and shares the same inherent human dignity. Everyone is entitled to the rights of citizenship without distinction as to race, sex religion, philosophical conviction, language or political outlook.

- Article 2. Every citizen has the right to life, liberty, and security of person. No-one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest of detention.

- Article 3. Every citizen has the right to freedom of conscience, to free choice and practice of religion, and to the free and open teaching of ethical and political beliefs. This includes the rights to freedom of assembly, the right to peaceable association, the right to petition, and the right to freedom of expression and communication.

- Article 4. Every citizen has the right to participate in the government of the country, and to equal access to its public service.

- Article 5. The basis of government is the will of the people. This is expressed in direct participatory democracy and free elections by secret ballot. The right of every citizen to follow his or her conscience, and to express his or her personal opinion, stands against any demographically contrived attempt at repression.

- Article 6. Every citizen has the right to education according to personal ability, the right to work, and the right to a standard of living worthy of a free human being. This right extends to food, housing and medical care, and to security against unemployment, illness, and disability.

- Article 7. Every citizen has the right to marry and found a family. Mothers, children, the aged and infirm deserve the nation’s particular care and attention.

- Article 8. Every citizen has the right to equal pay for equal work, and the right to join a trade union for the protection of workers’ collective interests, and these rights must be acknowledged by all employers.

- Article 9. In the exercise of their rights, citizens shall be subject only to such constraints as may be necessary to ensure recognition and respect for the rights of others and the welfare of the larger community.

It is intended that the European Convention on Human Rights, promulgated on November 4, 1950 in twenty-one countries, be made part of the internal domestic law of the New Ireland.

_________________________________________________________

Governmental structures

The system outlined here envisions a federation of the four provinces of Ireland under the co-ordination of a national parliament, with powers devolved through regional administrative councils to local bodies, so that at all levels citizens may have an effective voice in their own governance.

______________________________________________________________

Dáil Éireann

The New Ireland will have a national parliament, to which all citizens of the thirty-two counties will give common allegiance, and which will embody the unity and sovereignty of the nation as a whole. This parliament — a true Dáil Éireann — will have the responsibility of protecting the nation’s interests at home and abroad. All its actions will be governed by a constitution freely adopted by the majority of the people of the country.

_______________________________________________________________

Provincial government

Decentralised local government will be fundamental to the new system.

The four traditional provinces — Ulster, Munster, Leinster, and Connacht — have emerged as definite regions within the island of Ireland, with distinctive characteristics. Irish people in any region will be found to have a natural affinity — in culture, sport and economic interest — with those of their own province and county.

Uniting the historic province of Ulster will help eliminate the sectarian divisions of the past and realise the full potential for development of separated counties — especially Donegal, Derry, Tyrone, Fermanagh, Cavan, and Monaghan. The people of the long-neglected province of Connacht will find power to escape from their isolation. The people of the provinces of Leinster and Munster will be able to pursue policies that will secure them a more equitable and balanced form of development.

_______________________________________________________________

Regional boards

Regional boards will plan and oversee the economic, social and cultural development of areas within their jurisdiction. They will be served by secretariats employing modern means of administration while ensuring attention to and care for the problems of all the people of the region.

_______________________________________________________________

District councils

District councils will give people a direct voice in their own local governance, ensuring that their public representatives are more closely accountable to the electorate.

________________________________________________________________

Community councils

Community councils will give people the opportunity to improve conditions at parish level.

It is proposed that – to signify the beginning of a new era and the unity of the country around its geographic centre – Athlone be made the capital city of the New Ireland.

________________________________________________________________

National or federal parliament

The national parliament, Dáil Éireann — which will also be a federal parliament in that it will be drawn from the federation of Ireland’s four constituent provinces — will consist of a single chamber of about a hundred deputies, elected 50 per cent by direct universal suffrage according to the proportional representation system and 50 per cent in equal numbers from each provincial parliament. Each deputy (TD) would represent about 25,000 voters. The precise figure would be based on the ratio between the density of population of an electoral district and its geographical area.

Dáil Éireann will be representative of the whole of Ireland and elected by the suffrage of all its citizens. It will be the supreme national authority, acting in trust for the people. Its primary duty would be to uphold the Constitution and Charter of Rights adopted by the Irish people.

The national parliament, Dáil Éireann, will have the following special responsibilities:

a. defending the nation, physically and politically;

b. upholding the interests of the Irish people, and representing their concern for other people, in any international forum;

c. formulating Irish foreign policy, maintaining Irish neutrality and independence from all power blocs, including the EU, and seeking to secure a nuclear-free world; and

d. protecting and promoting Irish culture, language and literature.

Functions of the national parliament:

- the national parliament will control all powers and functions essential to the good of the nation;

- the national parliament will elect a President, who will serve as both Prime Minister and head of state;

- the national parliament will elect a Government, consisting of a limited number of ministers nominated by the President;

- the national parliament will secure the independence of the Supreme Court and of the judicial system as guardian of the Constitution;

- the national parliament will initiate national legislation, through any of the following agencies:

1. its own deputies,2. the central Government,3. a provincial parliament, or4. an initiative;

- The national parliament will adopt national legislation, either

a. directly, through its own deputies, or

c. by initiative in specified cases;

7. The national parliament will oversee collection of the federal revenue.

__________________________________________________________

Provincial parliaments or assemblies

Assemblies or parliaments will be established for each of the four provinces. The representatives will be elected by the people of each province according to a system of proportional representation.

The functions of the provincial parliament will be:

- to co-ordinate activity and development in the various regions in the province, with particular care for the unique character of the Gaeltacht areas;

- to initiate and promote legislation for the social, economic and cultural development of the people within the region, with the right to initiative; and

- to co-ordinate the development and expansion of third-level education;

- to collect provincial revenue.

______________________________________________________________

Regional boards

Regional boards will be established to promote and co-ordinate the economic, social and cultural affairs of clearly defined regions. The regional development board would be a single chamber consisting of:

a. representatives of district councils within the region concerned, elected according to a system of proportional representation, and

b. expert representatives appointed by the provincial parliament.

The regional board would have the following responsibilities:

a. to assess and co-ordinate the work of district councils in their regions;

b. to provide for hospitalisation and care of the young, aged and infirm;

c. to supervise regional planning;

d. to plan for economic growth;

e. to provide for cultural development.

The following regions are suggested:

- Connacht — two regions: North Connacht, consisting of Sligo, Leitrim, Mayo and the Boyle and Ballaghaderreen county electoral areas of Roscommon; and South Connacht, consisting of Galway, the remainder of Roscommon and the Claremorris/Ballinrobe area of Mayo plus the Gaeltacht are of Tuar Mhic Eide in South Mayo.

- Munster — four regions: Cork city and environs, South Munster, consisting of Kerry and North and West Cork; East Munster, consisting, consisting of South Tipperary, Waterford and East Cork; and North Munster, consisting of North Tipperary, Limerick and Clare.

- Leinster — four regions: Midlands, consisting of Longford, Westmeath, Laois and Offaly; East Leinster, consisting of South Louth, Meath, Kildare and Wicklow; Greater Dublin; and South Leinster, consisting of Wexford, Carlow and Kilkenny.

- Ulster — four regions: East Ulster, consisting of Antrim, East Derry, East Tyrone, North Armagh, and North and East Down; South Ulster, consisting of Cavan, Monaghan, part of Fermanagh, South Down, South Armagh and North Louth; Greater Belfast; and West Ulster, consisting of Donegal, Derry City and the Faughan and Limavady districts of County Derry, the Strabane and Omagh districts of County Tyrone, and most of County Fermanagh.

- All Gaeltacht districts would constitute a Gaeltacht Region.

Each region will be served by a fully staffed secretariat.

______________________________________________________________

District councils

A district council will consist of a single chamber elected by the people of a clearly defined area covering a population of 10,000 to 40,000 people.

District councils will have the following areas of responsibility:

- the welfare and security of the community and the application of the law in a humane and just manner;

- primary and secondary education;

- job creation, regulations governing employment and standards of work, trading practices, etc;

- local planning and environmental development;

- agriculture, fishing, and small industry;

- health centres, youth and recreational development;

- housing and control of rented accommodation;

- social welfare and social services.

Each district council will have a secretariat, where all services would be provided under the same roof.

______________________________________________________________

Community councils

Community councils will be voluntary bodies, representing close-knit communities based on parishes or other suitable centres, such as a district electoral area. To ensure the welfare of their people and the good of their communities, community councils will have the right of audience at all district council meetings.

________________________________________________________________

PLEASE NOTE: The above proposals are not definitive; they can and inevitably will be modified. Sinn Féin Poblachtach would in fact welcome constructive criticism of these proposals.

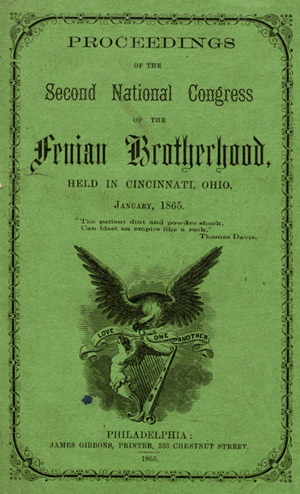

On July 29, 1848 the Young Irelanders made a half-hearted attempt to launch their uprising. It ended up being confined to a remote farmhouse in Ballingarry belonging to a widow by the name of Mary McCormack. There a small mob of rebels besieged a smaller party of Irish constables for several hours. When the siege was relieved by the arrival of police reinforcements, two of the besiegers had been killed and several wounded. The Young Ireland Revolt of 1848 or the Battle of Widow McCormack’s Cabbage Patch, depending upon from which political spectrum one observes the event, was over as soon as it began. But several of the Young Ireland fugitives who participated in the incident would become instrumental in the founding of the Fenians ten years later by making the 1848 Rebellion more important as a symbol in the future than anything it might have achieved in its own time.

On July 29, 1848 the Young Irelanders made a half-hearted attempt to launch their uprising. It ended up being confined to a remote farmhouse in Ballingarry belonging to a widow by the name of Mary McCormack. There a small mob of rebels besieged a smaller party of Irish constables for several hours. When the siege was relieved by the arrival of police reinforcements, two of the besiegers had been killed and several wounded. The Young Ireland Revolt of 1848 or the Battle of Widow McCormack’s Cabbage Patch, depending upon from which political spectrum one observes the event, was over as soon as it began. But several of the Young Ireland fugitives who participated in the incident would become instrumental in the founding of the Fenians ten years later by making the 1848 Rebellion more important as a symbol in the future than anything it might have achieved in its own time. Stephens was joined in Paris by thirty-two year old John O’Mahony, another fugitive of the 1848 revolt. O’Mahony studied at Trinity College in Dublin, although he never took his degree. He was part of O’Connell’s Repeal movement before seceding to the Young Irelanders in 1845. In Paris, Stephens and O’Mahony lodged together and would form a partnership—although sometimes strained—that would last until O’Mahony’s death in 1877.

Stephens was joined in Paris by thirty-two year old John O’Mahony, another fugitive of the 1848 revolt. O’Mahony studied at Trinity College in Dublin, although he never took his degree. He was part of O’Connell’s Repeal movement before seceding to the Young Irelanders in 1845. In Paris, Stephens and O’Mahony lodged together and would form a partnership—although sometimes strained—that would last until O’Mahony’s death in 1877.